Quick update: Since writing this post, I’ve started exploring agentic workflows and how they change the way I think about using AI for real work. There’s a lot to unpack there, so I’ll be writing a follow-up post soon.

I spent most of my weekend doing something slightly embarrassing for a software engineer who’s been “using AI” for a while: I tried to figure out why I’m so bad at prompting.

Not bad in the “I can’t get an answer” sense. More like bad in the “I know this could be way more useful, but I’m not getting consistent results” sense. And that’s been the blocker for me. Tools like Gemini and ChatGPT are obviously capable, but I kept feeling like I was leaving value on the table because I couldn’t reliably steer them.

So I decided to treat it like a proper debugging session. I read Google’s Gemini prompt design guide and took notes (this one: https://ai.google.dev/gemini-api/docs/prompting-strategies). A few things clicked quickly:

- Zero-shot vs few-shot prompting is a real lever, not just a buzzword. Sometimes you can ask for the thing directly, and sometimes the model needs examples to lock onto the style or structure you want.

- “Be specific” is still the rule, but the guide reinforced something I kept ignoring: specificity is not only about constraints, it’s about supplying the right context.

- Context placement matters. Putting the important stuff early tends to work better than tacking it on at the end like an afterthought.

Then I ran an experiment. I wanted to write UX copy for a landing page, end to end, including the hero section, feature and benefit blocks, testimonials, and FAQs. Normally I’d try a single mega prompt, get a mixed bag back, then waste time patching it. This time I tried a workflow that feels closer to how I actually work as an engineer: break the problem down, build up context, generate in pieces, and review at the end.

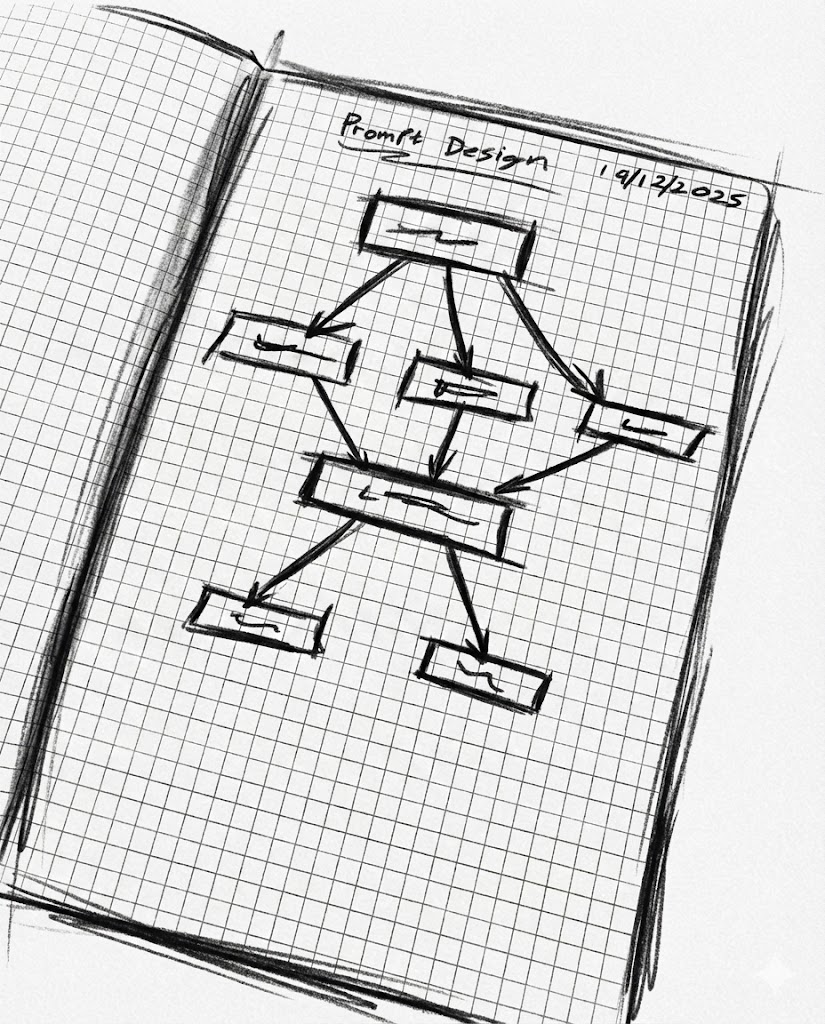

Here’s the flow that worked best for me.

First, I asked the model to give me a structure of questions it would need answered to do the job well. Not the final copy, just the interview. That prompt alone was surprisingly useful because it forced the model to define what “good input” looks like for UX copywriting. It came back with a long list of questions about the product, target audience, positioning, objections, tone, and success criteria.

Next, I took my messy, natural-language brain dump and used a second prompt to turn it into answers to those questions. This was the step that made me feel like I’d found a cheat code. Instead of me trying to write a perfect brief from scratch, I gave it the raw material and let it format it into something structured. Then I reviewed what it produced and edited anything that felt off or too confident.

After that, I wrote a new prompt focused on information architecture. Basically: given this context, propose the layout for the landing page. Hero, sections, flow, what comes first, what should be emphasized, where FAQs belong, and so on. This step used the structured context from the earlier prompts, which meant it wasn’t guessing as much.

Then came the actual writing. I created a prompt that acted like a UX copywriter, but with a narrow scope: write only one section at a time. Just the hero, or just the benefits block, or just the FAQs. I paired that section-specific prompt with the context we’d already built. The output got a lot cleaner once the model wasn’t trying to juggle the entire page in one go.

Finally, I ran a reviewer pass. I wrote a prompt that acted like a UX copywriting editor: take all sections together and check for consistency, repetition, tone drift, contradictions, and whether the copy still matches the original context. That last part mattered because it’s easy for these tools to “improve” things into something that sounds nice but isn’t actually true.

If you’ve read some of my earlier posts, you’ll know I’m not exactly a full-time AI enthusiast. I still think a lot of the hype is exhausting. But this weekend gave me a real breakthrough.

The trick, at least for me, is accepting that you can’t treat a complex task as one prompt. You have to break it down into small, specific steps. And if you don’t want to do that breakdown manually every time, you can write incremental prompts that guide the process for you.

The funny part is that, done this way, the whole thing starts to look less like “asking an AI for the answer” and more like collaborating with a slightly eager junior teammate. You give it the brief, you correct it, you ask for a draft, you review, you refine, and only then do you ship. Step by step, with validation at the end.

That’s what finally made these tools feel usable to me. Not magic. Just a workflow.